- Home

- Laura Gascoigne

The Horse's Arse Page 3

The Horse's Arse Read online

Page 3

Dirk was a liability, but he loved the guy. He was an artist, damn it, and he lived like one. He was generous too; he’d given the State a break on a group of barbed wire paintings. That didn’t happen often. They owed him a show.

Gaunt had been around for long enough to remember the days when public gallery curators relied on their connoisseurship to acquire work cheaply at the start of artists’ careers. You’d go to a studio somewhere in the sticks and buy a canvas fresh off the easel, still smelling of turps. Some artists you invested in never made it and were forgotten, others hit the big time and made up your losses. In those days acquisition budgets weren’t a problem. Today the State’s budget didn’t go anywhere because it was competing in a global market for contemporary artists with established reputations. A national gallery had to stock the big global brands to keep its place in the international rankings. And that meant buying at the top of the market, competing with Russian oligarchs and Arab princes.

How could the State plug the gaps in its contemporary collection when as fast as one was filled, another one opened? Gaunt stared down into the foundations yawning beneath him as into the abyss. Artists were prepared to be generous, but only for as long as their profiles needed raising by representation in a national collection. If a national gallery lost its global cachet, the game was up. True, the State’s new extension – when and if it opened – would create a buzz, but for how long? Another newer building would open elsewhere and Spritzer & Camorra’s egg would be yesterday’s omelette.

The single ray of light on the horizon was the emerging art scene in the Middle East. Acquisitions of Middle Eastern art would attract Community Cohesion funding, and prices hadn’t yet caught up. They soon would. Prices for Indian art had surged; the State had missed that boat. But contemporary art from Islamic countries was still affordable. Without a traditional culture of art collecting, they were starting from scratch.

Gaunt picked up the East Goes West catalogue and was leafing through it when his PA buzzed him.

“Aldo Camorra on the line,” she said. “Something about an eggshell finish?”

Chapter VII

A sea of bottle green broken with yellow, an expanse of pale red beach dappled with orange, a clutter of fishing boats hauled up above the shoreline, deep blue in shadow, orange in the evening sun. One boat coming in, another leaving for a night fish and various figures loafing on the shore watching the green of night descend to quench the yellow sun dipping behind the orange hills across the bay.

It didn’t need the signature underlined by the distinctive tail on the ‘n’ to tell you that the painting was by Derain. It was one of a dozen seminal views of the harbour at Collioure painted during that decisive summer of 1905 that Derain spent with Matisse inventing Fauvism in the East Pyrenean fishing village near the Spanish border. It was what auction houses called a ‘pivotal work’. They rarely appeared on the market and the last one to come up at Westerby’s New York had sold for $12m.

This one, what’s more, had a back-story to die for. It had been part of a Jewish collection of modern paintings seized by the Nazis in Paris in 1942 and added to the pile of art loot then being amassed at the Special Staff for Pictorial Art’s HQ in the Jeu de Paume.

The Meyers’ was not a big collection, but it was discerning. The Polish-born Joseph Meyer had adventurous taste. His fabric store in the Marais garment district didn’t make him the sort of money needed to buy the big modern art names of the day. By the time he started collecting in the 1910s Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin were out of his league and Matisse and Picasso were heading that way, although he did buy drawings. But artists one rung down the ladder he could afford. Like a genuine connoisseur, he understood that while artists of the first rank can produce duds, artists of the second rank can produce masterpieces. He bought top-notch works by what were then still affordable painters: Derain, Marquet, Modigliani, Vlaminck. His pictures were his children – his marriage was childless – and when he and his wife Lily died in Auschwitz, their collection was orphaned.

A single surviving nephew, Michael Slominski, had escaped from Warsaw on the last Kindertransport to leave for England in 1939 and eventually settled in Hampstead, where he scraped a living as a picture gilder and dealer in oriental antiquities. Michael had childhood memories of seeing pictures of his uncle’s art collection in a photograph album belonging to his mother, Joseph’s younger sister, and after the war he returned to Warsaw and traced the album, with other family keepsakes, to the possession of a former maidservant. But as he died in the early 1990s before the advent of the internet and digital databases of looted art, he had no way of discovering what had happened to the paintings. Nevertheless he made a will leaving the collection, along with the photograph album, to the Hampstead neighbour, Iris Goodman, who had looked after him during his final illness.

Now, during construction works for the new trans-European rail link through Stuttgart, the cache of paintings had come to light in the basement of a house due for demolition. How the collection had got there was a mystery. Modern paintings such as Meyer collected would have been designated by the Nazis as ‘degenerate art’ and, along with other ‘ownerless’ Jewish avant-garde art collections seized in Paris, would have been relegated to the so-called Martyrs’ Room at the Jeu de Paume, earmarked to be sold for foreign currency to fund Hitler’s Führemuseum of ‘approved’ European art in Linz. Banned as degenerate from entering Germany, modern collections ‘abandoned’ by Jews like the Meyers were dispersed in Paris and – unlike other Nazi loot later recovered from wartime storage in Germany by agents of the Allies’ Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives programme – disappeared into international collections, from which many works were only now resurfacing.

But for some reason, according to inventories kept at the Jeu de Paume, the Meyer paintings were included in one of the last rail freight shipments out of Paris in 1944, headed for the Heilbronn salt mines north of Stuttgart. One possible explanation is that the German dealer charged with converting the pictures into foreign currency preferred, with the end of the war in sight and hard times ahead, to squirrel them away for himself. Among the dealers approved by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, the special task force appointed by Alfred Rosenberg to sort through the loot at the Jeu de Paume, there must have been some who nourished secret tastes in degenerate art. Not all of them can have shared the Führer’s Sunday painter propensities – Expressionism, after all, was invented in Germany. But whatever the story, at some point before or after its arrival in Heilbronn the Meyer Collection became separated from the rest of the shipment. When the paintings were found in the Stuttgart basement they were still in an unopened crate bearing the original ERR label and stamp.

History might never know what had happened. Twenty years after Michael Slominski’s death, Iris Goodman was confined to a care home in Battersea suffering from Alzheimer’s. When first named as the beneficiary of Slominski’s will she had initiated a search for the paintings, to no avail. Now her inheritance was to be sold and her only benefit would be an upgrade in accommodation to a ‘studio care suite’. Her Australian brother-in-law, a solicitor in Sydney, had taken charge of matters. He had put the pictures into the hands of the London dealer James Duval, one of the reclusive Slominski’s few friends. Duval collected netsuke and Michael had found him a few bargains. He had also restored the gilding on some antique frames.

Some of the paintings had suffered damage in the damp basement and needed conservation. It would be a while before they reached the market. But the Derain looked as fresh as the day it was painted.

Chapter VIII

Up against the moody violet of The Seventh Seal, which Pat had yet to steel himself to scrape off, the Derain harbour painting looked startlingly bright.

He wondered if he might not have overdone it. He’d had a completely free hand with the palette, as the photocopy Marty had given him was black and white. But he’d spent several studious mornings with the Derains in the State Galle

ry and, allowing for the fact that the State’s only landscape from the artist’s Fauve period was a London painting of the Thames and therefore muddier, he reckoned he’d pitched the colours more or less right. By a happy accident he’d since come across a reproduction of a Collioure painting in an old calendar saved from a car boot sale, and had inched up the colour key to match.

The paint-handling he was pleased with; it had life. If it was broken colour you were after, Patrick Phelan was your man. Just as well, as Marty’s photocopy was so small and blurry he’d had to improvise the brushwork. All the same, it was dull work copying. He’d had more fun with the Degas, but he wasn’t grumbling. Three grand a pop was an absolute fortune, the sort of money he hadn’t seen in years. Alright, if he was honest, ever. And Moira had come over all sweetness and light since he’d handed over the first wodge. She’d gone back to calling him by her pet name Feeley – he hadn’t been called that in twenty years. Best of all he’d been able to go mad in Cornelissen’s and splurge on handmade Michael Harding paints.

For a hit of colour you couldn’t beat those babies; they packed a punch like Rocky Marciano. Too good to waste on a load of Collioure cobblers – Rowney’s cheapo Georgian student range had been good enough for that. No, the Hardings were reserved for The Seven Seals. The tubes were lined up in their racing colours, ready for the off.

Normally when a painting was finished Pat turned it to the wall to stop it nagging. Even when grown-up and ready to leave home, pictures went on clamouring for attention. Inadequately launched young adults, was that what they called them? Just like Marty, still a child at 35. But the Derain was no child of his, so he wasn’t bothered. When The Seven Seals were unveiled in all their glory, the little French Fauve would pale into insignificance.

Marty had mumbled something about a Modigliani, but until a photo materialised Pat was free. With the decks luxuriously cleared for the heptatych, the day stretched out before him like a willing woman.

Still, the usual tremor of anxiety heightened Pat’s excitement as he turned the seven canvases round one by one and stood them around him in a half-circle like a choir round a choirmaster. A ragtag choir, raw-throated and under-rehearsed. He had to get them singing in tune and in unison. Would they?

The White Horse, The Red Horse, The Black Horse, The Pale Horse, The Souls of the Slain, The Great Earthquake, The Seven Angels: the seven seven-footers lining the walls of The Shed jostled for attention while he stood in the doorway and watched them.

“Well now, my troublesome beauties, which is it to be?”

Not The Seven Angels, he would let them lie; he was still smarting from his bruising of the week before. The angels and their trumpets were too much. The sea of glass mingled with fire worked, and Jerusalem like a rare jewel built of jasper, but those other gemstones with tarts’ names – emerald, chrysolite, beryl – were over the top. The Seventh needed purification by fire. He’d come back to it another day.

Not The Pale Horse, either. He felt too sanguine for that this morning, ditto The Souls of the Slain. It was between the white, the red and the black horse and the earthquake.

He was in the mood for a shake-up. He went for the earthquake.

Sun black as sackcloth, full moon like blood and stars falling to earth as the fig tree sheds its winter fruit when shaken by a gale. Sky vanishing like a scroll rolled up, and four angels holding back the winds of the earth…

St John was the biz. In the midst of the maelstrom, it was the image of the fig tree that struck him. He had made it the focus of the picture, positioning it between the black of the sun and the red of the moon, with silver stars raining through its bare branches.

The sticking point was the sky vanishing like a scroll rolled up. He had considered slashing the top of the canvas and rolling it back a la Lucio Fontana, but slashing his way out felt like an admission of defeat. What went for Slasher Fontana wouldn’t go for Feeley Phelan. Still, the fact remained that painting things appearing was one thing and painting them vanishing was another. How to paint absence? That was the Holy Grail, the colour that didn’t exist. Rembrandt came close in his putty-coloured shadows, but Rembrandt’s earth palette was too much of this earth for Pat.

He decided to start at the bottom where the great multitude stood with palm branches in their hands before the throne and the Lamb, and work up. Once the bottom was sorted, the top would sort itself.

As he squeezed out the rich oil colours from the new paint tubes onto his palette, Pat felt their intensity like a chemical shot in the arm. The only way was to go for it, no half measures.

“I know your works,” he shouted aloud, “you are neither cold nor hot. Would that you were cold or hot! So, because you are lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew you from my mouth.”

Quite right too, the bastards had it coming.

For the robes of the sealed made white in the blood of the Lamb he had chosen Naples yellow, hotter than white and, more importantly, louder. The multitude had to cry out in a loud voice, while the rich and the strong – the doomed – were skulking in their caves hardly daring to breathe for fear the Lamb heard them. The marvel of Revelation was that it touched all the senses: synaesthesia on a stick. Silence, though, was as difficult to paint as disappearance. If the sealed were yellow, what colour were the doomed?

Pat was vacillating between Payne’s grey and indigo, testing them out in his mind to hear how they sounded, when the cadmium orange clang of cowbells broke in on his thoughts and threw out his calculations.

Hellfire and damnation! Ten o’clock on a Wednesday morning. Who could it be?

Not Ron. His neighbour’s habitual line of attack was from the flank through the gap in the hedge. Ron never made formal complaints through official channels.

If he ignored the interruption it might go away. He squeezed out an inch of indigo, mixed in some ultramarine and tried it for size on the caves to the right. Their mouths fell away to infinity. Ha! He was just beginning to relish the ensuing silence when the orange clang cut in again from the veranda, louder this time.

Fire and brimstone!

He laid down his brush, wiped his hands on his fuchsia shirt and crossed the garden to the back door in the side alley. Through the fox-flap of broken planking at the bottom he could see a pair of policemen’s boots.

Too late to beat a retreat, the policeman would have seen his.

He drew back the bolt, scraped the door open and found himself looking at a young woman dressed in black with a camera bag slung over her shoulder. She had long dark hair and heavy square horn-rimmed glasses, and when she smiled she showed good strong teeth.

“Tammy Tinker-Stone,” she held out her hand.

Pat stared at her blankly. Was she a model? Remove the glasses and all that black and she wasn’t bad-looking. But he was busy now, she could come back later.

“I’ve brought the camcorder,” she smiled, tapping her bag.

Now he remembered. Bugger. She was one of Marty’s fashionable young artist friends, the woman who wanted to film him painting.

Why? And why in the name of Jesus had he agreed?

He led the way back to The Shed with a heavy tread. No one had ever seen all the Seals together and this bird with the bovver boots was a total stranger. But he’d promised Marty, and he owed him. No time to cover their modesty now.

The young woman stopped in the doorway.

“Wow,” she said, “what is it?”

“It’s a heptatych,” mumbled Pat, “of The Seven Seals.”

“Its amazing,” she said, unpacking her camera and going straight for the jugular: The Seventh.

“I can see the water,” she pointed at the sea of glass, “but where are the seals?”

Pat decided it was useless explaining.

“I haven’t put them in yet,” he said.

Chapter IX

In his office overlooking Leg of Mutton Yard, Nigel Vouvray-Jones scrolled down the list of consignments for June’s Impressionist & Mod

ern sale and pushed another Nicorette through the foil. The two patches he was already wearing weren’t working. He needed a top-up.

February’s Contemporary auction had gone better than expected, thanks to Warhol. OK, Warhol wasn’t exactly contemporary – he’d been dead for a quarter of a century – but he was alive in spirit, and his Factory had been so productive during his lifetime that, despite his Foundation’s best efforts to choke off supply, there was little danger of stocks running out.

If RazzellDeVere’s Contemporary Art Department had depended on the living they’d have had to shut up shop. True, contemporary artists like Seth Poons and Cosmas Byrne who had gone platinum during the boom years were in no danger for now. The recession might have dampened the western appetite for art about consumerism, but in the east it was just taking off. The problem was that the new breed of international collector only wanted blue chip investments, and two blue chip artists didn’t make a contemporary art market.

Even alpha dealers like Orlovsky were feeling the pinch. Bernie had enough stock in storage to singlehandedly keep the contemporary art market afloat for a decade, but unless he got top whack he wouldn’t sell. Once prices in an artist had been allowed to fall, the market in that artist was finished. And what collector today would pay top whack for a conceptual piece by an artist like Jason Faith, even with an Ars Nova certificate attached? When it came to the crunch, concepts were two a penny. Today’s art investors wanted a bigger bang for their buck – a goat with golden goolies, not an empty room. In the current economic climate, the only thing conceptual art had going for it was low storage costs.

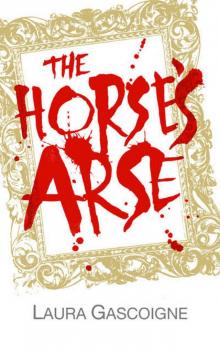

The Horse's Arse

The Horse's Arse