- Home

- Laura Gascoigne

The Horse's Arse Page 2

The Horse's Arse Read online

Page 2

He flicked through the pages of muzzy black and white photos.

A Matisse Odalisque, £30m at today’s prices. A Cézanne Still Life with Compotier, possibly as much as £40m. That would be greedy. He paused at a Harbour at Collioure by Derain. That was better.

The photo was faded but clear enough to make out the composition. The colours you could only guess at, though with Derain there was a fair amount of leeway.

It had been in the collection of the Meyer family in Paris. The perfect lost picture. The trouble was that as soon as it was ‘found’ the family would come out of the woodwork to claim it. Unless, that was, the family was lost too.

He had a bit of research to do.

Chapter IV

Daniel Colvin had only been at Marquette a month when the office politics started. Fay had asked him to report on a rumour that RazzellDeVere had been buying in paintings by Dirk Boegemann, represented until now by the Orlovsky Gallery, and were sitting on a pile of them waiting for his prices to rise.

The recession had come at a bad time for Boegemann, just when his paintings had passed the six-figure mark and were headed for the stratosphere. Now rumour had it that the State Gallery was planning a show. The State was normally wary of contemporary painting – its conceptual bona fides were always hard to establish – but Boegemann’s ghostly monochromes wouldn’t frighten the horses, and RDV were reputedly offering sponsorship.

Public gallery rubberstamps painter formerly represented by leading commercial gallery and currently being stockpiled by auction house. It all sounded distinctly dodgy to Daniel. He did a bit of scratching around, interviewed a few people – even got the elusive Jeremy Gaunt on the phone thanks to the director’s PA mistaking him for a young architect working on the new State Gallery extension. Gaunt said nothing was planned, which amounted to a quote. Daniel’s piece was filed and flat-planned when suddenly, without an explanation, Fay pulled it.

Daniel was sure Crispin Finch was behind it. Fair enough, he understood Finch protecting his turf. He’d been with the magazine since it started. But having one’s first news feature spiked was not a good omen. And now Fay, who had been flirty before, was ignoring him.

At this rate he wouldn’t be in the job past Easter, and he needed to keep it if he was going to finish his art history thesis. So he said nothing when he was shifted to a routine item about a British Council-funded touring exhibition called East Goes West, a collaboration between the State Gallery and Khaleej Museums Authority in the United Arab Emirates.

The exhibition paired young British artists with Middle Eastern contemporaries working in similar ways. Daniel ran his eye down the list of exhibitors. Mervyn Burke, he noticed, was twinned with a Lebanese artist called Salim Murr, who collected autographs of people called Muhammad. Jason Faith was matched with Iraqi artist Jahmir Zerjawi, who turned bombed-out buildings into installations. And Celeste Buhler was partnered by Iranian woman artist Afshan Zardooz, who had filmed herself in a white burqa against a white wall so that all you could see of her were her eyes.

From the illustration point of view, it wasn’t promising.

Daniel opened one image after another. An empty bombed-out room, another room empty but for a disembodied pair of eyes, a sheet of paper empty apart from a signature.

There must be something better. He opened an image called The Nile Feeds Itself, and smiled.

It was a contact sheet of photographs by an Egyptian artist, Karim El Sayed, documenting the dismantling of a reed-and-daub hut. The first picture showed the hut with smoke curling through a hole in the roof; the last showed the ashes of the fire into which the final reeds have been fed. It was paired with Cordelia Markham’s exploding shed.

Another one for the thesis on Sheddism. Daniel copied it onto a memory stick and slipped it in his pocket. It still surprised and delighted him to receive confirmation of the centrality of the shed to the history of art: an archetypal symbol of creation from Bethlehem on.

He filed the copy to Crispin and attached the image.

“Thanks,” came a curt reply, “but why the shed?”

The piece was eventually published under the title ‘Middle East Agreement Signed’ and illustrated with two signatures – ‘Muhammad’ and ‘Mervyn Burke’. The second signature was attached to Coffee Ring No. 23.

Chapter V

It was a Poussin day, with a lapis-blue sky and streaky puffs of white cloud sailing over The Shed of Revelation at the back of no. 15 The Mall.

How grand that sounded! It still amused Pat to say his address without adding the postcode. Since moving to the street all those years ago he’d discovered that it shared its name with a dozen Malls in London, not counting the one The Queen lived at the end of. There were Malls in Bexhill, Brentford, Bromley, Croydon, Dagenham and Surbiton, all of them laying claim to the definite article. Pat’s was in Bounds Green, Haringey. He and Moira had moved to the area more than thirty years ago and brought Martin up there, if you could call it upbringing. Then Moira had pushed off, Martin had gone west and he had been left in sole occupation, an ageing bohemian beached in the ’burbs.

From his kitchen window Pat was distantly aware of an expanse of violet signalling to him from inside The Shed. With a sinking heart, he recognised it as the latest incarnation of the upper section of The Seventh Seal. Over the decades he’d spent tussling with that painting, it had been halfway round the colour spectrum and back. Now he saw with a sickening clarity that cobalt violet wouldn’t do the job either.

He wished to God he’d turned it to the wall and tucked it in properly the night before. Now the wretched thing would be clamouring for attention on a Blue Orange morning when he needed to focus on the class. Pictures were like children, never left you in peace. Out of sight, out of mind was the only answer.

As he shaved around his goatee at the kitchen sink, the unforgiving light of the bright March morning revealed in the soap-spattered glass that his hair colour also needed attention. His barnet was starting to look like Davy Crockett’s hat, with the black tips turning red then white as they neared his scalp.

Insufficiently realist, too expressionist. He picked up the bottle of Just For Men off the windowsill and shook it. Enough for the eyebrows, maybe, but they could wait. Who was he kidding? He was old enough to be Suzy’s father. Ah well, he sighed contentedly, you never knew.

The Blue Orangers were the amateurs Pat taught in The Shed on Friday mornings. He’d started the class for the money, placing an ad on the community notice board in the local Budgens, but carried on for the love. The group had been coming in various forms for years, although it had only recently acquired its name.

It was Wolf, of course, who was responsible. Pat had set up a still life of apples and oranges in a bowl and was preaching his usual broken colour sermon, urging the class to underpaint in complementary colours that would break through the picture surface and make it quake. A fought-for image, Pat maintained, was an image worth having. But Wolf, a wartime refugee and a diehard pacifist, refused to fight on principle and persisted in painting his oranges orange.

Wolf insisted he could only paint what he saw; when he tried to make things up they just didn’t work. (They didn’t work that well when he didn’t but Pat wasn’t going to be the one to tell him.) Meddling with reality, he said, messed up the shadows and shapes needed shadows to hold them down. Without them everything sort of floated off. So while Pat had his back turned that particular morning, Wolf had tiptoed over to the table with a brush-load of ultramarine and painted all the oranges in the fruit bowl blue.

Pat was smiling at the memory when the phone rang.

At that hour of the morning it had to be Moira about money. She’d have it soon enough. He let it ring.

Late news from Marty was that his millionaire collector friend was cock-a-hoop about the Degas. Now, apparently, he wanted modern masters for his mansion and he’d given Marty a list of half a dozen. At three grand a pop Pat would be coining it. The downside was that t

he collector had now decided he wanted copies of existing works, which made Pat’s job that much more boring to do. But he wasn’t grumbling. If the guy could piss away that much on copies, what wouldn’t he pay for the genuine article? The heptatych was in need of a home, or better a chapel. He wondered if there was room for a chapel in the mansion’s grounds.

The lime green of Pat’s trousers clashed briefly with the grass as he hurried across the garden carrying a safety lamp, a colander, a bunch of yellow fabric freesias and some purple tissue paper. The lamp had come from a neighbour’s skip, the freesias from a church bazaar, the tissue paper from the offy and the colander from Dino’s late mum. “The only thing she left me,” the lugubrious Italian had lamented to him, “and it had holes in.”

It had the makings of an interesting still life, Pat thought. The whiplash curve of the metal lamp hook certainly had dynamic potential. The flowers could have done with a vase, but there was always the coal scuttle. And the colander would have looked better with a load of apples, if he hadn’t eaten them. Never mind, he’d fill it with coal from the scuttle.

Good colour combo, yellow, purple and black.

Inside The Shed The Seventh Seal assaulted his senses. In the light of day the violet was a complete disaster. For a moment last night he’d had the colours in perfect equilibrium, all the plates spinning in the air at once, then he’d trowelled on the violet and dropped the lot. Now the balance was shattered he’d have to scrape off.

He saw it now, too late, clear as mud. The whole thing hinged on the mighty angel with a face like the sun and feet like pillars of fire. The angel had to burn up the competition, and by swamping everything in violet he had put the fire out. The hiss of the soggy embers brought him close to tears.

The morning after could be worse with paintings than with drink or women.

He turned the picture wearily to the wall and looked around to find Irene behind him. She had a feline knack of suddenly materialising.

“Hello old cat,” he greeted her absently. “To what do I owe the pleasure?”

“You booked me for a session, remember?”

He didn’t, but he hadn’t the heart to send her away. She was probably counting on the money. So when the class arrived they found a model reclining on the yellow bedspread with a scuttle of flowers and an overhanging skip light.

Pat was dithering over where to put the colander full of coal. In honour of the lapis-blue morning he’d based Irene’s pose on the sleeping nude in Poussin’s Nymphs and Satyrs in the National Gallery, but the still life elements were giving him grief – though he liked the way the curve of the skip light hook rhymed with Irene’s right breast.

He’d arranged the flowers in the scuttle with the tissue for foliage. The vertical flue of the wood-burner stood in for the tree under which Poussin’s abandoned nymph luxuriates, and the skip light hung just to the right of the trunk where the face of Poussin’s leering satyr peeks out. After trying the colander in several places he settled on a position in the left foreground, making a diagonal with the skip light through the nymph’s head.

“Nude descending a chimney,” quipped Wolf as he got out his paints.

“Got it!” said Pat. Still life problem sorted. He told the class to give it the Cubist treatment.

As they got stuck into the subject a hush descended, punctuated by the occasional squeak of charcoal and rattle of pencils in a case or brushes in a jar. It was the sound of parallel play not heard since childhood, the happy hum of absorption in the perfectly useless.

Naturally the Cubist theme went to pot. As hard as Pat tried to challenge his class to do things differently, they always ended up doing them the same. Wolf always produced the same naive paintings with glaring local colours and heavy black shadows. Suzy always turned out the same bright and breezy pictures on the safe, Scottish Colourist side of Fauve, with all the women looking exactly like her. Here she was, at it again, putting her own head on Irene’s body.

But what a head it was, thought Pat, sneaking a sideways look at the heart-shaped face with its insouciant, slightly sniffy nose framed by floppy golden hair and dangly earrings. You could see the temptation.

Grant, meanwhile, created boxy 1950s abstracts out of whatever you put in front of him. He could have been staring into Marilyn Monroe’s wide-open beaver and he would have filed it all away neatly into modular storage. The ordered mind of a solicitor, Pat supposed. And Dino… well Dino was just Dino. It was impossible to put a name to the amorphous splodges even now appearing on his canvas. If Dino’s first artistic language was Italian, then he was a macchiaiolo with a speech impediment. Yet the deliberation he brought to his task was awesome. Look at him now, dotting in the holes in the colander with the same fevered concentration he had just applied to Irene’s right nipple.

As for Yolande, Pat suppressed a sigh. Yolande was a one-trick pony with the stubbornness of a mule. Her approach to every subject was to home in on an area of detail – half an orange and the end of a banana, or a shoulder and an armpit – and blow it up to fill the entire canvas. She brought things so close to the picture plane you could have smelled them, if it had helped you to work out what they were. This morning she was focusing on the junction between the pink of Irene’s exposed throat and chin and the galvanised steel grey of the background scuttle, with its protruding triangle of purple tissue. Wolf once joked that if you taped all Yolande’s life drawings together they’d add up to one enormous, bill-board-sized nude. Yolande wasn’t amused. The others had learned to put up with Wolf’s jokes but Yolande didn’t have a sense of humour.

The only member of the class who found Wolf funny was also the only born artist among them. Maisie was a natural. Pat had spotted her eye for colour in the charity shop, where she’d pick out clothes from the bags for him and hide them out the back. Maisie was in her 70s, she had never painted but she took to broken colour like a duck to water. Her drawing was erratic but her paint surfaces shimmered like Bonnard’s. She responded to the subject. And sure enough, when Pat did the rounds, hers was the picture that thrummed with life.

He held it up for the group’s admiration.

“All singing all dancing,” he cried, “that’s how we like our scuttles!”

Maisie peeped over the top of her glasses and smiled, a brittle little smile that lit up her face like an involuntary reflex. Suzy and Yolande looked deflated.

Pat went over to examine Suzy’s painting. The skip light, scuttle and flowers were perfectly drawn and the treatment was Cubist, but the nude was young and slim with a turned-up nose.

As he looked from Suzy’s nymph to Irene and back, he felt a dangly earring brush his cheek. He swallowed.

“It helps to look at the model from time to time,” he said.

Chapter VI

The bright spring sun threw the giant shadow of a pterodactyl across the wall of the director’s office on the top floor of the State Gallery.

The first time it had happened Jeremy Gaunt had jumped, but the crane had been working outside his window for weeks now and he was used to it. Eventually, he hoped, it would stop bothering him. With the foundations of the new extension only just laid, the pterodactyls would be nest-building for months. His main concern now was that the shadows kept moving. If they froze it meant the money had run out.

Adaptable creatures, human beings, got used to anything. How could Gaunt have guessed when he got his first regional gallery directorship in his thirties, a rising star in a newly legitimised contemporary art world, that he would spend his fifties at the top of the gallery tree directing architects rather than artists? Then it was all about shaking up the British figurative art scene with cutting edge Minimalism imported from America. Now it was about shaking down American billionaires to raise the funding for cutting-edge extensions.

He went over to the window and looked down into the foundations that gaped beneath him like a clutch of pterodactyl chicks waiting open-beaked for their mother to appear with food. And here she was

returning to the nest with a 12m steel I-beam – another £3,000 worth – dangling from her jaws. At this rate the tens of millions of funding he’d wheedled out of a reluctant Department of Arts & Community Cohesion would be spent before the building showed above the ground. And in these lean times there’d be no more where that came from. The rest would all have to be got from private sources.

Meanwhile, of course, building costs were soaring. Spritzer & Camorra’s egg-shaped design had seemed a nice idea during the boom years when galleries were sprouting extensions like designer fungi, but now it looked extravagant and unnecessary – which, in private, he was forced to admit it was. God only knew what they would fill the place with. The ostensible argument for government funding had been that the gallery needed more wall-space for its collections, but apart from the fact that the egg had no vertical surfaces, the State collection still consisted mainly of Victorian paintings that could never be hung in a modern gallery. So the space would have to be filled with a rolling programme of temporary exhibitions, which meant more curators and more marketing staff. More money.

As another I-beam sailed past the window, Gaunt thought back to the events of the night before. That business with Dirk and the redhead after the party had been a mistake. He could get away with that sort of thing in Basel but not here. If the story got out Virginia would never forgive him. Not that it would damage his reputation with the public; he was aware that people thought him sexless. Well, there was life in the old dog yet.

He felt his face muscles contract momentarily as he remembered the scene in Dirk’s hotel room. He really ought to exercise them more often, then it might not look as if he had jaw ache every time he smiled. He was conscious of how unnatural it appeared. He’d caught himself in the mirror once and it had wiped the smile off his face.

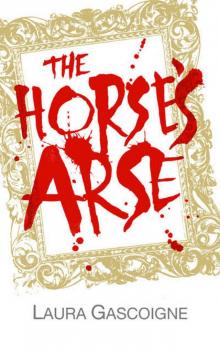

The Horse's Arse

The Horse's Arse