- Home

- Laura Gascoigne

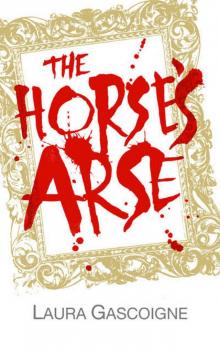

The Horse's Arse

The Horse's Arse Read online

THE HORSE’S ARSE

or

THE SHED OF REVELATION

Laura Gascoigne

To the Unknown Artist

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Chapter XXIX

Chapter XXX

Chapter XXXI

Chapter XXXII

Chapter XXXIII

Chapter XXXIV

Chapter XXXV

Chapter XXXVI

Chapter XXXVII

Chapter XXXVIII

Chapter XXXIX

Chapter XXXX

Chapter XXXXI

Chapter XXXXII

Chapter XXXXIII

Chapter XXXXIV

Chapter XXXXV

Chapter XXXXVI

Chapter XXXXVII

Chapter XXXXVIII

Chapter XXXXIX

Chapter L

Chapter LI

Chapter LII

Copyright

Chapter I

“Left a little… Up a little. Turn your head to the window so the light falls on your nose – that’s it – and dream. Dream of your first lover… where is he now? Perfect. ‘My old flame, I can’t even think of his name…’ Now bunch your hair and hold it over your ear – so – and draw the comb across con amore, like you’re playing the cello.”

Music, that’s what was needed. Dvořák. Would Degas have listened to Dvořák? Dvořák was Czech and Degas was French, and anyway they didn’t have records then. He must have painted in silence.

Pat considered this possibility, rejected it and crossed the studio to find the cello concerto. He handled the 1970s Philips record player con amore. Top of the range machine, a bargain buy. And look, the shade of orange matched his socks.

As the recording scratched into life, a shaft of dusty spring sunlight broke through the window and transfigured the middle-aged woman on the couch, heightening the white of her skin against the red of her hair and setting the yellow throw beneath her aglow. Pity about the tongue and groove behind. He’d have to bodge the Chinese wallpaper.

Killer combo, cerulean and cadmium yellow. He rattled around in his box of pastels and picked out a blue one. A few deft strokes of cerulean over cobalt, some buds of lemon yellow, a tracery of burnt sienna and bang! The tongue and groove was fin de siècle Chinoiserie.

Pat consulted the open book on the painting table. Hmmm. He’d have preferred the pose of the D’Orsay picture with the model on the floor completely nude, one leg tucked in, the other bent in front and both arms raised above the shoulder, brushing the hair up from the nape of the neck. But that was a bit athletic for Irene.

Good old Irene. Must have been a beauty, and still moved her old bones like a cat. There was something naturally statuesque about her. She didn’t perch like an amateur, she sat. And the pose of the Hermitage picture came out sexier if approached from the left, exposing both breasts and the model’s mouth.

Irene had a good mouth. He touched it in with Indian red. It yawned.

“Time for a break, I’ll put the kettle on,” said Pat, returning the Indian red to the box with special care.

Nice of Martin to get him Unison pastels. Quality gear, soft on the hands as talc and saturated in pigment. Hand-rolled between the thighs of Northumbrian maidens, with none of the usual binder muck thrown in. Not much different, he reckoned, from the pastels Degas used. Martin could be surprisingly generous sometimes.

Pat crossed the patch of garden to the kitchen quickly. Since the second hip replacement he’d had a limp, but he always crossed the garden quickly in case Ron next door came out and collared him.

That was the trouble with the ’burbs, your neighbours. Ron was still hopping mad about The Shed despite the fact that it had improved the property. Before it went up he’d never stopped complaining about the tip at the bottom of the garden. So what if Pat hadn’t got planning permission? Since when did you need permission to plan? Next thing you knew, you’d need a licence to dream.

Anyway it wasn’t any business of Ron’s what went on at the bottom of Pat’s garden. Some people had fairies, Pat had The Shed of Revelation and a bloody fine specimen of a shed it was too. Dino had done a fearless construction job, far better than Martin. If Martin had built it water would be coming in. Shame that someone as brilliant at building should be so hopeless at painting. Ah well, Dino was a 3-D man.

Returning with the mugs of tea, Pat risked a momentary halt in mid-garden to admire The Shed of Rev’s front elevation. How Dino had managed to build a double-fronted cabin with a veranda entirely out of skip wood was a miracle. All that was needed for perfection was a rocking chair, but in a rocking chair he’d be a sitting duck for Ron.

He could see Irene standing framed in the left-hand window in her old kimono, holding a cigarette and wearing the exact expression he’d been after. That was a picture worth painting, but it would have to wait. Funny how many artists painted women from behind looking out of windows and how few thought of doing them from in front.

So many pictures to be painted, and so little time.

On his way back in with the teas, he raised the mugs in a silent toast to the stack of tall canvases propped against the wall to the right of the entrance. “You too my beauties, I haven’t forgotten you,” he whispered mentally. “You’re the real McCoy. But first we must get Degas out of the way.”

The money would keep Moira happy, that was the main thing. Not that she ever complained, but that made things worse. If her useless excuse for a second husband would only get off his arse and keep her in the style to which she should have been accustomed it wouldn’t be an issue, but every time Pat thought of her scrubbing floors on her hands and knees his heart sank. Beautiful bright Moira working as a cleaner, while he swanned about the place being an artist. Was it self-indulgence? It was what he did. It was a job, unpaid perhaps but a job all the same. Wait until The Seven Seals were opened, then the world would see that Patrick Phelan had not been wasting his time. When the heptatych landed, the world wouldn’t know what hit it.

He put the teas down on the table, came up behind Irene and slipped a hand still warm from the mug under her kimono. It squeezed her left breast.

A bit on the soft side, but it still felt good.

Chapter II

Martin Phelan was acting like he owned the place as usual, although it wasn’t his house. But it was his handiwork, and he was entitled to feel proprietorial. OK, so the orangery wasn’t strictly finished, the landscaped garden was a building site and the lily pond was leaking, but those were all things that could be fixed. Nothing that couldn’t be fixed with money, and Orlo had plenty.

The rain was a piece of luck anyway, it would keep people indoors. Not so lucky for the papier mâché sculpture park at ICE, but hey! It was all about entropy. The coke was kicking in and he was feeling positive. He refilled his glass from the catering table, ignoring the bar staff, and went to work the room.

If a bomb went off this

evening, Martin was thinking, it would wipe out the whole London contemporary art world plus a sizeable chunk of the global one. On the eve of the first International Contemporary Equity art fair, ICE – a joint venture between auction house RazzellDeVere and Marquette magazine – everyone who was anyone was in town and all of them were on Orlo’s guest list. For a recession, they were putting on a good show.

Over by the fireplace (yes, a fireplace in an orangery – Orlovsky asked for one and the customer is always right) Martin could see Fay Lacey-Piggott, Marquette’s editor-in-chief, in conversation with Nigel Vouvray-Jones, senior director of RazzellDeVere. On the sofa beside them, between two women in white and black dresses – the white monochrome minimalist Celeste Buhler and the papier mâché sculptor Heather Manning – sprawled the Dutch painter Dirk Boegemann, his pale blue eyes fastened drunkenly on a voluptuous redhead who was listening with rapt attention to Jason Faith. Jason had won last year’s Ars Nova Prize for his Empty Room. Martin couldn’t imagine what the redhead found so gripping – the guy was on the dumb side of laconic, but he played in a punk band and she looked like a groupie.

Martin could see that Bernice was boring him. He watched him move her aside to allow a skinny kid with nipple rings in a torn black singlet slip past to the bathroom with an older man in a pearl grey suit. The skinny kid was Puerto Rican performance artist Enzo, a specialist in public bloodlettings, and the older man was northern art collector Godfrey Wise. At a party last year Enzo had gone to the toilet and slashed his wrists, and Godfrey obviously didn’t want him repeating that here. The incident had got into the tabloids, causing embarrassment. Martin watched them emerge minutes later looking chipper. He smiled as Mervyn moved Bernice aside again to let them pass without any visible interruption to the verbal flow.

Anywhere else this sort of discretion would have been unnecessary, but Orlovsky was a stickler for appearances. Even at home he had his gallery goons on the door. One of them had frisked Martin playfully on the way in and now he was dishing out the same treatment to the art dealer James Duval, who was not looking happy. Never mind, thought Martin, he’ll cheer up when he hears about the Degas.

Orlovsky’s goons were recruited from the Hoxton gay mafia, and you didn’t mess with them. The one by the bar was keeping an eye on Dirk. Martin saw him stiffen as the ascetic figure of Sir Jeremy Gaunt, director of the State Gallery, appeared in the doorway with the flicker of a smile of greeting on his face. A barely perceptible shiver ran through the room.

Security didn’t lay a finger on Gaunt, but when video artist Tammy Tinker-Stone crossed the room to film his arrival on her phone, one of the Hoxton heavies took it off her. She shrugged and smirked and came over to where Martin and Duval were standing.

“A fair cop,” said Martin.

Tammy had not yet won the Ars Nova and everyone knew she was gagging to. She’d been shortlisted the year before for Gutted, her video collage of football managers reacting to missed goals, part of a series exploring the contemporary symbolism of the tragic mask. Now she was collecting smiles on the faces of art world insiders, but it wasn’t going well. It lacked the drama and emotional range of the stadium. Recently, though, a new idea had occurred to her, a good one if she could find the right person for it.

“I need an artist,” she announced.

“Take your pick,” said Duval, waving a dismissive arm around the room.

“Not that kind of artist. A proper artist.”

“Proper?” Duval raised a tired eyebrow.

“A painter, I need a painter. Not like Dirk,” she jerked her head towards the catering table against which the Dutchman now had the redhead pinned, “an old-fashioned painter. One who uses, you know, colours, an easel, palette, brushes. The works. One who’s serious about the whole operation. I want to record the creative act, the image taking shape on the canvas, the whole performance. I want to do painting as performance art. Know anyone?”

“You could ask my Dad,” said Martin, “if you don’t mind him jumping on you.”

“Is he good?”

“What’s good?” asked Duval with effete distaste.

“I mean good like a master, like, oh, Degas. Whoever.”

Martin glanced at Duval.

“He’s good like Degas.”

“Can I have his number? Bugger, they’ve got my phone.”

She pulled a pen out of her bag and scribbled the number Martin gave her on the back of her hand.

“By the way,” Duval turned to Martin after she’d gone, “my conservatory’s leaking.”

Chapter III

The halting drip of water into a bucket beat an erratic rhythm to Duval’s thoughts as he sat brooding at the desk in his book-lined study. In the gloom of the basement the desk light cast a warm bright circle on a pastel drawing of a bare-breasted redhead sitting on a yellow bedspread combing her hair.

It was unmistakably a Degas, though not a known picture, which could have been an advantage but was actually a problem. Why would an uncatalogued Degas suddenly surface after more a century? The image was evidently a close relation of the oil painting, Woman Combing her Hair, in the Hermitage – the same acid yellow bedspread, electric blue wallpaper, nacreous skin and auburn hair. But the pose was different, and the breasts were a little less pert.

Typical of Martin to start at the top; it always had to be big stuff with Martin. He should have warned him to stick to the 20th century, when the materials would be less of a giveaway – though these days who checked? With a modern artist, too, it was more likely that unknown pictures might have fallen through the cracks, especially with an artist of the second league. With a big name like Matisse or Picasso who had been catalogue-raisonnéed from here to there, provenance became a major problem.

He picked up an eyeglass and examined the surface of the drawing. It was masterful. The deftness of touch, the ragged outlines, the messiness… This was not the work of a copyist but an artist. Pat Phelan had brought something to the table. Duval wondered what his own work was like. He touched a corner with his little finger and the pastel came off. Good, at least he hadn’t used fixative. Sensible choice pastel, dry medium.

People had laughed at Donald Rumsfeld, but his famous distinction wasn’t so stupid when applied to art. In matters of provenance you could have ‘known knowns’ and ‘unknown unknowns’, but an ‘unknown known’ was as questionable as a putative WMD and more open to inspection. Better, if you were going for a big name, to make a copy of a picture that was documented but lost. A ‘once known known’.

He propped the pastel up against the wall. As a fake it was probably worth a grand; as a Degas it was worth upwards of £30 million.

“Art is a rum do,” he mused out loud, “Turner was right.”

Until two years before, Duval had been Head of Impressionist & Modern Art at London auction house RazzelleDeVere, but they had rewritten his job description during the credit crunch and given the post to someone younger and cheaper. His wife was working so they weren’t on the street, but the independent dealership he had set up was taking time to establish.

With the new top-lit extension, if it wasn’t leaking, he could at least show clients pictures at home. But London was awash with established dealers who were struggling as the auction houses swallowed more and more of their business. Not content with using guarantees to hook the sorts of nervous sellers who would previously have preferred private treaty sales, the big auction houses were moving into other areas of the market. In the past few years RDV, for example, had been operating as a dealership on its own account. The auction house had been buying in paintings by rising stars and sitting on them until opportunity knocked in the shape of a public gallery show that would raise the artists’ profiles and their prices. Now it was taking a punt on ICE to become a major player in the contemporary art market.

The problem with historic art, for both dealers and auction houses, was that the supply of good stuff was drying up. And the private dealer’s professional advan

tage – the leisure to chat up rich widows – would soon be nullified when the supply of rich widows with blue-chip art collections ran out. Now especially, in a harsh financial climate, collectors wanted gold-plated investments like the Giacometti Walking Man that recently sold at auction for £65m. That was the genuine article though, heaven knows, there were enough dodgy Giacomettis around. More than half the drawings in circulation were probably fakes. The artist’s estate was fighting a losing battle.

None of this, though, bothered people like RazellDeVere’s director Nigel Vouvray-Jones as long as they could go on shifting stock. Turnover was all that mattered now. Sack the experts and take on more marketing staff. Billionaire collectors in emerging markets – China, India, Russia, the Gulf States – didn’t give a hoot about the educated views of experts, they preferred the soft sell approach of Miss Cassandra Pemberton with her Armani glasses and her Prada handbag.

Serve RDV right if he slipped one past them. They had it coming.

But fooling the auction house, he knew, would be the easy bit. Artists’ estates presented a more serious problem. There was always the risk of running up against surviving relatives who could recognise an artist’s handwriting in his brushwork. The auction houses pretended they could, but they were bluffing. Most of the current crop of ‘experts’ couldn’t smell a rat up their own trouser leg, and they were now so desperate for throughput they hardly bothered sniffing.

Well, not altogether true – they looked at documentation. If an ‘unknown known’ suddenly appeared out of nowhere there would be questions asked and demands for paperwork. Where did it come from? What exhibitions had it been shown in? Why didn’t it feature in any catalogues? Why no photographs?

Photographs were the sorts of hard proof you needed. But if a painting had been photographed it would be traceable to a collection. Unless, of course, the collection had subsequently been lost.

Duval jumped up and went over to his bookshelves. In the top left-hand corner, gathering dust, he found it: Volume II of the Répertoire des biens spoliés en France durant la guerre 1939-45, the record of Nazi war spoils assembled by the Bureau Central des Restitutions after World War II. Volume II dealt with paintings, tapestries and sculptures. He had brought it with him from Razzells when he left. They’d never miss it.

The Horse's Arse

The Horse's Arse