- Home

- Laura Gascoigne

The Horse's Arse Page 19

The Horse's Arse Read online

Page 19

At the lifts she dusted herself off and adjusted her hair. The sheepish-looking usher handed her the hat and was rewarded with a smile that deepened his embarrassment.

“Excuse me,” Daniel butted in, “you’re a friend of Patrick Phelan’s aren’t you?’

“Yes,” she replied tentatively, wondering how he knew.

Daniel scribbled his address on a page of his pad and tore it off.

“If you see him, could you ask him to get in touch with me? There’s a painting of his I’d like to buy.”

Chapter XXXXVIII

‘L-O-V-E’ read the fingers holding the brush; ‘H-A-T-E’ read the fingers holding the palette. With intense concentration a prisoner was adding the finishing touches to his entry for the Levene Awards.

Before being banged up, none of the men in Mantonville Rec Room would have had anything to do with art other than nick it. Ponce about with a paintbrush? You had to be joking. No money in it, and no respect.

Inside was different. People accustomed to active lives – carjacking, ram-raiding, safe-blowing, assault and battery – could go stir crazy cooped up in a cell 24/7. Blokes signed up for classes out of desperation. You’d get hard nuts volunteering for ‘drama therapy’ or ‘creative writing’. Posh birds with accents off of the BBC telling you to “act out your personal problems and negative feelings”.

“Alright, darling. How long have you got?”

This was different, this was doing something with your hands. Nothing as constructive as cracking a cashpoint, but still something. There was an end product that wasn’t there at the beginning. Plus if you got selected for the Levene Awards your work got shown in a public exhibition. Your painting got out on licence even if you didn’t.

Best thing about the art class, though, was the teacher was an inmate, doing time for fraud. Faking pictures. The guy was crazy, Irish, off another planet but basically a geezer and bloody brilliant. He must have been because the picture he faked sold for 16 million quid and would be hanging in a fucking museum if he hadn’t been rumbled. Respect.

There was none of that personal problem shite with him, he just shoved something in front of you and told you to paint it, for better or worse – preferably for worse, as he said that generally turned out better. Some of the stuff he came out with was bonkers. Last week the class was sat here painting this scissor jack with a bunch of plastic grapes and a statue of a naked woman – still life for lifers he called it – when he said he’d rather do life with a real naked woman and – get this – that he’d applied to the guv’nor for permission and the guv’nor had said no. Told you he was crazy. So then he says the only alternative is for one of us to strip off, like studio assistants used to do for Michelangelo or Raphael or one of them Italian Renaissance ninjas, and the rest of us to draw in the tits from imagination. The answer to that, obviously, was no too.

Pull the other one, mate, it’s got knockers on.

So there we were at 3pm on a Thursday afternoon when we could have been watching the snooker, sleeves rolled up, painting plastic grapes like our lives depended on it with him stood over us like an Irish Leonardo dishing out advice. “Gently does it, you’ve got all the time in the world. You’re doing time, remember? Hold your brush like this, like you’re turning a key in a lock. Not breaking and entering, no – you own the place. Everything in the picture belongs to you, but if you burst in on it too suddenly it’ll scarper.”

Nuts, like I said. When he wasn’t standing over you, you had to watch him or next thing you knew he’d be painting your portrait. Done Jake’s the week before last, caught him in action with a look on his face like he’s painting the Mona Lisa. In actual fact it was a bag of spuds and a cheese-grater and Jake’s picture looked like a pile of sick and a bucket, but he got the little bastard down pat. Spitting image. His chin was green, his nose was purple and his hair was blue, but his missus, when she saw a photo, said it looked more like Jake than Jake did.

Funny thing is, at the beginning his colours looked daft but after a while they sort of grew on you. On a sunny day you’d catch yourself looking at the shadows of the bars on the cell wall and wondering what colour they really were. Before you’d have just said grey and left it at that but now you’d stare at the blimming things for hours just thinking about it. Though if anyone asked you what colours they actually were you wouldn’t have a bleeding clue.

The other week Lynton was painting these oranges blue and Paddy was stood behind watching him.

“That’s an interesting shade you’ve chosen,” he says.

“Yes,” says Lynton, “it goes with the maroon bananas. You know what? I’m beginning to see what you mean about colours talking to you.”

“You’ve been spending too much time alone mate,” says Jake. “What are they saying?”

“Fuck off,” says Lynton.

We’ll miss the old nutter now they’ve moved him to an open prison.

Chapter XXXXIX

Rain was falling in sheets: nice weather for ducks, crap weather for skateboarders. But one hardened individual was aquaplaning down a ramp in the StateSkate park, the cord of his anorak hood pulled tight around his nose, his sleeves pulled down over his fists like an amputee.

Look ma, no hands.

Dry in Zubarrah, thought Jeremy Gaunt as he watched the water level rising in the skate park’s troughs, and the ghost of a smile momentarily troubled his face.

Who would have guessed that Martin Phelan, of all people, would turn out to be a knight in shining armour? Thank God and his old-fashioned upbringing that he’d never been rude to him. Noblesse oblige, his father had taught him, for a very good reason – you never knew who might come in useful one day.

MoMAK, Khaleej’s new museum of modern art, was taking the Wise Collection off his hands, all bar a few plum pieces the State was hanging onto. And next year the Khaleeji Royal Family would be sponsoring an Arab Art Spring at State Gallery, all expenses paid: catalogue, installation, reception, security, the works.

In the meantime there was the Ernst van Diem exhibition, dirt cheap to mount, as it was mostly ‘collection of the artist’. Since Westerby’s bought out the Orlovsky galleries they had taken Ernst on, and he was acquiring quite a reputation. Every dog has his day. In a slower economy the market was warming to late developers, artists with a more considered vision. While Cosmas Byrne’s dot paintings were losing their fizz, van Diem’s vibrant canvases were hitting the colour spot with collectors. His naïve daubs in the style of Karel Appel were being touted as Dutch Neo-Expressionism. Needless to say the success of his former assistant had got right up what remained of Boegemann’s septum, but there was nothing to be done. Since the disastrous failure of his RDV auction the dismal Dutchman’s prices had collapsed, and now no one would touch him.

Gaunt noticed that the rain collecting in the troughs had formed a moat around a tumulus-shaped hump at the edge of the skate circuit near the gate to the car park. He followed the figure of the sodden skateboarder as he looped a couple of laps around it, scooted backwards, built up speed and flew over the top, landing with a swoosh of spray on the other side.

Chapter L

Duval watched the ducks diving in the prison pond. There was something reassuring, he’d discovered, about hitting rock bottom. Divorced, a convicted fraudster and a bankrupt: when he got out, it could only be a fresh start.

They’d given him three years, meaning two with good behaviour, and after one they’d moved him to Bridge Open Prison. He’d be out in four months, and thanks to Martin, he had his future mapped out.

How wrong you could be. The sale of the Degas that he’d assumed would be a disaster had been a godsend. It was the Derain that had got him arrested, while the Degas was now sitting pretty on the walls of the National Museum of Khaleej and Martin had been generous enough to save him a share. Generosity seemed to run in that family. He was still astonished by Patrick Phelan’s altruism in taking the rap for his son. Would he have been that generous in his posi

tion? He couldn’t say, he’d never had children.

Thank Christ he too had had the sense not to finger Martin, for entirely selfish reasons admittedly – he’d been desperate to keep the loudmouth out of court. Well, he’d learned a lesson: never underestimate a con artist. A Martin with a clean record had turned out to be of infinitely greater use than a Martin without. Without the Degas sale he could never have passed himself off as an art world mover and shaker in Khaleej. And without his, Duval’s, art expertise and contacts, he would never be able to maintain that position.

When he got out, Martin was putting him on commission to source Impressionist and Modern pictures for the new museum, money no object. Since shelling out $100m at auction for a Warhol Car Crash at Westerby’s New York, the Khaleeji Royal Family had decided to make future acquisitions by private treaty. Arabs liked to keep their dealings personal, and there’s no one quite like a con man for the personal touch.

As long as Martin stayed away from architecture. Rain wasn’t a problem in the Gulf, but islands can sink.

Chapter LI

In his only suit, Dr Daniel Colvin waited under the Strand entrance to Somerset House for the rain to stop. It was pissing down, he hadn’t brought a coat and the number 4 bus stop for Finsbury Park was a hundred yards away in the Aldwych.

Having just been awarded a PhD from the Courtauld for his thesis on Sheddism Daniel ought by rights to have been walking on air, but the pavement was one big puddle and his shoes leaked. After two minutes of watching the steady precipitation he got tired of waiting and decided to run for it. For some strange reason, though, when he stepped out from under the archway he remained dry.

The large black umbrella over his head seemed to explain it.

“Dr Colvin?”

The voice behind him made him jump.

“I meant to surprise you, though not like that,” said Yasmin, shaking raindrops off her curls. “I got off early but not quite early enough. Sorry to miss the ceremony. How did it go?”

“Pretty well, actually. Nobody laughed.”

She dropped the umbrella to hug him, soaking them both.

“Come on, I’ll buy you a drink. Where’s good around here? I know! The Waldorf Astoria.”

“You’re crazy! They’ll never let us in.”

“Of course they will, with you in that suit.” She pushed her glasses down her nose appraisingly. “You scrub up well. Plus I’ve got something to celebrate too. You know that picture you reproduced in your Indian supplement? A gallery in Mumbai saw it and they want to represent me.”

“That’s fantastic news!” It was his turn to hug her. “The drinks are on me.”

The upside-down umbrella was collecting water.

“If we get any wetter,” she said, “they won’t let us in.”

He picked up the umbrella and shook out the water as he steered her purposefully towards the kerb.

“Watch out!” she shouted as they narrowly missed a cab that was pulling out after dropping off a fare. “You know what they say in India? A doctor is only a doctor when he has killed one or two patients. But you don’t have to take it literally, Dr Colvin. It’s only a proverb.”

Chapter LII

“Nice stamp,” said the female warder, handing Pat a letter. “Where’s that from then?”

The design showed a falcon hovering over a pearl-shaped island, the falcon red, the island silver, the sea blue.

“I don’t know,” said Pat, extracting the contents. He didn’t recognise the stamp but he knew the writing. That childish, unformed script could only be Marty.

He pulled out a sheet of paper folded in four and, with a slight tremor in his fingers, opened it. The words ‘Desert Pearl Royal Residence and Spa, Khaleej’ were embossed in gold capitals along the top.

“Dear Dad,

Apologies for not getting in touch sooner. As you know, letter writing’s not my strong point and since arriving in this earthly paradise I’ve been run off my feet.

I hope they’ve been treating you alright in chokey. You’re a dad in a million – I’ll never forget what you’ve done for me. Unfortunately what with one thing and another I can’t be there to meet you when you get out, but you must fly straight out here – I’ll send you the ticket.

This place is brilliant. Sun, sea and sand – not your usual subjects, I admit, but you always seem to find something to paint. A pair of the Cat’s Pajamas the barman mixes and, I promise you, everything looks rosy. The weather’s fantastic, it never rains. The desalinated water tastes like piss, but who waters their whiskey?

To get down to business. I’ve been in touch with James in Bridge Open Prison and he’s agreed to represent you. There’s been a lot of interest in your work – you’re a famous painter now Dad – and James is planning a retrospective when he gets out.

But here’s the big news now, listen to this. A month ago Her Highness Sheika Fatima, the third wife of the Emir in charge of this paradise isle, went to Houston and saw the Rothko Chapel and came back wanting something similar here. She started complaining that the Pearl Island development is soulless – she was educated in Paris – and she’s decided a secular chapel is what’s needed. Her idea was that non-Muslim foreign tourists could use the place to recharge their spiritual batteries, and with a central location in the Oasis Mall the locals could also use it as a chill-out space while shopping.

She wanted big paintings like the Rothkos but less abstract, with more stuff going on people could tune into, and she asked if I could recommend an artist. Well of course Dad I immediately thought of you. I rang Dino and told him to go to The Shed and take some pictures of The Seven Seals. She’s seen them, loves them, she’s over the moon. All we’re waiting for is the nod from you to ship the pictures over and we can get on with designing the building. I’m working with a team of international starchitects, so no worries.

Fan-bloody-tastic or what?

I enclose a plan of the design so far.”

Love

Marty

PS. You’re the best dad in the world.

PPS. I had to change the title for religious reasons, hope you don’t mind.

Pat’s hands were shaking as he felt in the envelope and pulled out two folded sheet of tracing paper. One was a ground plan of a chapel-shaped space with a seven-sided apse at one end; the other was an elevation of the apse, with the Seals in place.

A lump formed in Pat’s throat. It was all he’d dreamed of.

“Chapel of Contemplation”, read the caption, “with Patrick Phelan’s ‘The Seven Heavens’ installed.’

Seven Heavens? What the hell!

Any reservations Pat felt were swept away in a breaking wave of parental affection.

Marty had done him proud. Blood was thicker than water. Seven seals, seven heavens, what was the difference? Meaning lay in the eye of the beholder. What mattered was that the paintings had a home. And what a home it would be! An Arabian palace.

“Good news?” The warder was watching him with interest. “You look like you’ve died and gone to heaven.”

Pat jumped. He’d forgotten she was there.

Not a bad looking woman, actually – good strong features in a pleasant-shaped face.

“My dear, you don’t know how right you are.”

He stuffed the plans back into the envelope and before she could stop him he had grabbed the warder round the waist and was waltzing her around the mail-room cheek-to-cheek singing ‘Heaven, I’m in heaven…” in a fruity baritone.

“What on earth are you doing?” yelped the warder, who was too young to know the Irving Berlin classic.

“I’m not on earth,” sang Pat, “I’m in heaven… heaven, and my heart beats so that I can hardly speak…”

“Let me go before I have you put in solitary,” she struggled to say, but she was laughing too hard to get the words out.

Pat felt the laughter shake her diaphragm through her uniform. Nice body, on the chunky side but firm. Surprisingly small waist ove

r spreading hips.

He wondered if she’d pose for him. Never hurt to ask.

Copyright

Published by Clink Street Publishing 2017

Copyright © 2017

First edition.

The author asserts the moral right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior consent of the author, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that with which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN: 978–1–911110–87–3 PAPERBACK

978–1–911110–88–0 EBOOK

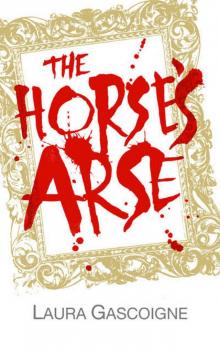

The Horse's Arse

The Horse's Arse