- Home

- Laura Gascoigne

The Horse's Arse Page 17

The Horse's Arse Read online

Page 17

On his way out Daniel asked the Head of Press if she would let him have a copy of the video, as Marquette would like to run a profile of the Ars Nova winner in the following issue.

Chapter XXXXIV

When the party broke up, Jeremy Gaunt went back up to his office. It was after ten but he had another hole to fill, this time in next year’s exhibition schedules.

The previous summer, when it had become perfectly clear that the money to finish the building works would not be forthcoming either from government or private sources, the painful decision had been made to mothball the State Gallery extension until further notice. It had fallen to Gaunt to break the news to Orlovsky that the headline Russian exhibition planned for the launch of the new extension would have to be cancelled.

Gaunt was surprised at how badly he took it. Fair enough, the Orlovsky Gallery had put work into the show, but the dealer seemed to take it personally. Gaunt had never seen him lose his composure, let alone his legendary temper, which he was shocked to find himself on the receiving end of. Orlovsky raged about having delivered the Wise Collection into his hands, only to be rewarded by a kick in the teeth. His Russian backers, he warned – indeed almost threatened – were not used to this sort of treatment. It was the last they would be contributing to the State Gallery’s newly established Russian Acquisitions Fund, or to any other funds for that matter.

He got so worked up that Gaunt worried he would have a heart attack. To calm him down, he had to promise to make space for a smaller exhibition in the main building. It wouldn’t get the fanfare of the launch exhibition but it was the best he could offer in the circumstances, as he was sure Orlovsky understood. On the State Gallery’s part, it would mean cancelling an exhibition that had been years in preparation.

And now, just when planning on the Russian exhibition should have been gathering pace, Orlovsky had vanished off the face of the earth. If the show failed to materialise, a three-month gap would open up in next year’s autumn programme that would be almost impossible to plug. Exhibitions were complicated enough to organize without the problem of procuring loans at short notice.

Where were the institutions willing to lend to a show that was due to open in less than a year’s time? Gaunt’s mind was a blank, but at least here in his eerie, with the place to himself, he had the rare luxury of space to think. He relished these moments of solitude in the vast empty building. Alone in his control room on the seventh floor, he felt like the brain in the State Gallery cranium.

Tonight, admittedly, the brain was a little fogged. It wasn’t alcohol. Gaunt never drank at receptions; in his position he couldn’t miss a beat. No, it was cumulative exhaustion from rattling around year in year out on the hamster wheel of gallery administration – something of which he was forcibly reminded every day by the Jötnar & Rasmussen fairground wheel recently installed in the gallery atrium. Made of recycled pumpjacks supplied by sponsors Oil Britannia, the wheel had attracted environmental protests but was proving very popular with younger visitors who, with their numbers swelled by the protestors, were giving a welcome boost to attendance figures.

Gaunt’s mind was not on the Danish duo, however. He was thinking about the Tammy Tinker-Stone video of that old artist pottering about in his shed. A dying breed, he’d thought while watching it, and the thought had filled him with a sense of loss he couldn’t dispel.

It was that video that had won Tinker-Stone the prize. Gaunt had driven the decision through over the heads of the other judges, two of whom – led by Orlovsky’s exhibitions director Tom Jonson – had been gunning for the Taiwanese circuit boards. Jonson dismissed the video as lacking in conceptual rigour; he found it whimsical, sentimental and old-fashioned. Even its kooky subtitle, ‘The Way Forwards Is Backwards’, was retrograde.

Apparently that was the old painter’s motto. Thinking of it now, Gaunt broke into a smile, one of those secret, unforced, oddly youthful smiles that could still, on rare occasions, crack the carapace.

No possibility of the State Gallery going backwards; onwards and upwards was the only course. Nothing could be allowed to interfere with the march of artistic progress dictated by the market. Still, though a backwards move was out of the question, it occurred to Gaunt as he looked out of his window onto the building site below, half abandoned since the cranes migrated north, that a sideways move might get him out of not just one hole, but two.

It hadn’t escaped the notice of his paymasters at the Department of Arts & Community Cohesion that the highest attendance figures at a contemporary art exhibition that year had been for a show of graffiti artist POG in his hometown of Plymouth. During its three-month run at the City Art Gallery POG’s show had attracted 300,000 visitors from all over the country, many of whom had never been in an art gallery – a demographic to die for.

Those figures would guarantee the Plymouth show a coveted ranking in Marquette’s annual league table of the world’s most popular art exhibitions, a list the State Gallery always struggled to get onto. Despite all the media coverage and the televised presentation, the Ars Nova audience could never come near that figure, especially not with this year’s unspectacular line-up. Art critics might get off on ‘conceptual rigour’ but for the general public it spelled ‘rigor mortis’. Well, Madani’s horses should pull in the odd punter who’d wandered in for a ride on the big wheel. He wondered if Jötnar & Rasmussen could be persuaded to build a rollercoaster next year.

Plymouth, imagine. The State was prepared to lose out to the Louvre and half the public museums in Japan, where gallery-going was a national religion, but Plymouth? That was a real slap in the face. The very thought of it, in fact, was enough to shake him out of his funk.

As he watched the huge ovoid hole of the stalled extension’s foundations filling with water from the November rains, an idea that could solve the Russian and the egg problems at a single stroke began to take shape in Gaunt’s mind. Why not turn the site into the world’s biggest skate park? Throw it open to top international graffitists from around the globe – America, Australia, Brazil, Japan – and expose POG for the provincial player he was!

With an interactive zone for local taggers and workshops run by global graffiti names, it would tick all the funding boxes: regeneration, multiculturalism, audience-creation… Meanwhile the galleries that had been reserved for the Russian exhibition could host a show of related works by graffiti masters, delivering teenage taggers into the arms of the Education Department who could then redirect them towards the permanent collection. The exhibition would be temporary but the skate-park semi-permanent, remaining in place until the rest of the funding for the extension was forthcoming – if necessary, until kingdom come. And the marvellous thing about the whole scheme was that it would cost next to nothing.

Viewed from his seventh-floor window, the housing estates of South London spread out beneath Gaunt like a carpet of LEDs pulsating with potential visitor numbers. As he gazed out over them, his peripheral vision was disturbed by a slight movement on the building site below. A gang of workmen in hard hats appeared to be digging a trench in the shadow of the construction hoarding near the site entrance.

Odd, as the site had been more or less deserted for months. At this time of night it must be emergency drainage work – there had been worries about standing water affecting the foundations. And in fact the men were lowering a half-pipe into the trench. A half-pipe! The coincidence struck Gaunt as prophetic. For some reason the men seemed to be working in darkness, apart from the light cast by the street lamp on the other side of the hoarding. Strange that nobody had said anything about it, but minor problems were often kept from him. He sometimes suspected that he was perceived as a control freak.

He shut down his computer, switched off the office lights, took the lift down to the ground floor, bid the security guards goodnight and took the back exit to the car park serving the construction site, now deserted apart from his Toyota Prius and a builder’s van.

As he got into his car he

could hear the workmen on the other side of the hoarding speaking a language he didn’t understand. Polish probably, though it lacked the note of complaint he associated with Polish. To his ears it sounded more like Russian.

The State should really be employing British workers; he’d speak to the architects’ office in the morning. But in the morning other things intervened, and he forgot.

And so it was that Orlovsky’s State burial went undiscovered.

Chapter XXXXV

Yasmin suppressed a yawn as she dumped the stack of envelopes on her desk.

Nothing interesting ever came by post these days; it was either junk mail or forms. Before the cuts there had been a secretary to sift it, but now that Yasmin had to open the mail herself she put the chore off until the end of the day to stop it taking the edge off the morning.

This evening she was running late and she’d arranged to meet her mum at the station with Sami. Since the Orlovsky case had turned into a murder inquiry – although no body had so far been found – her security detail had been moved to other duties. The advice from on high was that it was safe to bring her son home. Sami was missing his mum, and he was missing school.

The train was due into St Pancras in 40 minutes. If she prioritised, she could pick out the urgent-looking letters and leave the rest until tomorrow morning. She riffled through the stack of envelopes, pulled out a small jiffy with a Special Delivery stamp and tore it open. A CD fell out accompanied by a folded proof of the front page of November’s Marquette.

On the CD was a Post-it note with the cryptic message: ‘FF 40 mins’.

She could have left it to the next day, but it was Daniel’s writing. She slipped the disk into her CD drive and fast-forwarded. To her astonishment, she found herself watching a film of Patrick Phelan working on one of those seven canvases in his shed.

How did Daniel know about the Phelan case? She hadn’t said anything. It was still under investigation.

It was a moment before she realised he didn’t know. What he was drawing her attention to was a little painting of a harbour scene leaning up against the wall behind the artist – the exact same painting as was staring up at her from the front page of next month’s Marquette. The difference was that the Marquette version had an antique gilt frame and had just been sold by the auction house RazzleDeVere for £16m.

The Phelan case was getting more and more interesting. Scribbling ‘I’ll explain tomorrow, Yasmin,’ on the Post-it, she dropped the CD and proof on Burningham’s desk on her way out.

Chapter XXXXVI

‘£16M DERAIN A FAKE? BOUNDS GREEN ARTIST ARRESTED IN DAWN SWOOP’. A special report by Marquette’s Daniel Colvin appeared on page 3 of The Times of Friday 6th November.

“In the early hours of yesterday, two weeks after auctioneer RazzelDeVere’s sale of Derain’s ‘lost’ Harbour at Collioure for £16m broke auction records for the artist, Metropolitan police officers assisted by specialists from the Art & Antiques Unit raided a suburban semi-detached property in Bounds Green. A tip-off had led detectives to the studio of 67-year-old artist Patrick Phelan, a part-time art teacher, who was taken in for questioning on suspicion of forgery.

“A search of the artist’s studio in a shed at the back of the property revealed, among a cache of unidentified paintings, what appeared to be a half-finished copy of a Modigliani nude. Police also took away photographs thought to depict missing paintings and a reference work on artists’ signatures.

“The suspect was taken to Paddington Green Police Station and later released on bail.

“On the basis of evidence collected at the Bounds Green property police later visited a basement flat in Chelsea, home of the art dealer James Duval, former head of the Impressionist & Modern Art Department at RazzellDeVere. Officers were seen removing some 30 pictures from the flat, mostly landscapes and nudes by an unidentified artist.

“Mr Duval is assisting police with their enquiries.

“In a separate development, the UK border agency has been alerted to look out for a third suspect, the interior architect Martin Phelan, son of the artist, reported to have taken delivery of a consignment of canvases from the Bounds Green address in the past few weeks. It is feared he may attempt to leave the country, if he has not already done so.

“The clients of Martin Phelan’s architectural practice included many prominent figures in the London art world, among them the missing gallerist Bernard Orlovsky. This has prompted speculation that the gallerist’s disappearance might be connected with an art forgery ring, though that seems unlikely. Orlovsky dealt almost exclusively in contemporary art and no evidence of contemporary forgeries has come to light.”

Fay blew on the sliced ginger tea that had replaced macchiatos in her regime since the health farm visit. She was proud of Daniel, and of herself. What a find he was! The young man had a genius for investigative journalism. He was a little cagey about divulging his sources, but on his record so far she was prepared to trust him. He kept his ear to the ground. His exclusives were raising the magazine’s profile, and the circulation figures were showing the effects.

Only last week she had been invited on News.am to discuss Orlovsky’s disappearance. Her fear now was that she’d lose Daniel to a mainstream paper. But no, he was too interested in art and the mainstream press were only interested in art prices or crimes. All the same, he’d earned a promotion. Crispin Finch had lost his nose for the business. All that guff about the fake Derain on November’s front page had been a huge embarrassment. It didn’t help that the mainstream papers had all made the same mistake. Marquette should know better.

Crispin was getting past his sell-by. OK, he was younger than her but he didn’t look it, with his papery skin and rheumy eyes. She was tired of his grumpy presence around the office; he was always in a pet about something these days.

Chapter XXXXVII

In an airless room on the first floor of Southwark Crown Court, Judge Levene removed his wig from its steel box and shook out its tails.

The horsehair, he noticed, was looking tired and fuzzy. It was time he acquired a new one, but not worth the investment. He would be retiring next year.

He put it on, tucked his hair inside it – at 69, he still had hair of his own – and checked that the tails weren’t caught under his robe. The rush-hour tube to London Bridge had been suffocating and despite the air-conditioning in the courtroom, it was the sort of day when you sweated into your wig. But this morning’s proceedings ought to be a breeze. One of the accused had pleaded guilty and the other hadn’t a legal leg to stand on.

It had been an odd sort of trial. In his 10 years on the bench Levene had never seen the public gallery so full in what was not, after all, a celebrity case. It was a more colourful crowd than usual and, as far as the women in the front row went, noticeably more attractive.

A surprising turnout for two pensionable fraudsters. Wives and girlfriends? Unlikely. Artists’ models? Possibly. The women certainly carried themselves well. There was one in particular, a woman of a certain age, who had something almost majestic in her bearing – the way the head sat on the neck, and the neck on the shoulders.

Married happily to the same woman for forty years, Solomon Levene did not regard himself as a judge of horseflesh, though he was something of a connoisseur of art. A dabbler given to donning a panama hat on holiday and painting watercolour landscapes for relaxation, he was a firm believer in the therapeutic benefits of art. Three years earlier, he had started the charity New Life for Lifers to bring art into prisons, a cause to which he was hoping to devote his retirement. He collected contemporary paintings in a modest way, under a self-imposed – well, wife-imposed – limit of £500. It was astonishing what you could buy for such small sums if you knew what to look for. And Levene had an eye. He could tell that the fakes at the centre of this case were extraordinarily good.

After 40 years in the law, 10 on the bench and 30 as a criminal defence barrister, Levene was looking forward to retirement. He was tired

of court business and, unlike colleagues who had grown comfortably into their roles, felt increasingly uneasy as the years went by about adjudicating over other people’s lives. The older he got, the more unfathomable life’s mysteries appeared to him and the less qualified he seemed to be to pronounce upon them. But this case dealt with an area of life he knew something about, and he had to admit that he was rather enjoying it.

New faces in the media gallery too, he’d noticed. Arts press, presumably – not the usual crowd of jaded legal journalists. At the start of the trial, when the artist stood to enter his plea, the judge had seen a young reporter grinning as he took notes. Some of the jurors too had been suppressing smiles.

The man had certainly been unconventionally dressed. Instead of the customary dark suit for a court appearance, he was wearing a turquoise-striped gondolier’s shirt with the sleeves rolled up and a pair of mirror sunglasses hooked into the neck. His bottom half was clad in maroon trousers, and Levene thought he caught a flash of canary yellow socks.

Perhaps the defendant felt that his guilty plea absolved him of the need to impress the court. His associate, who had pleaded not guilty, wore a suit. Still, there was something oddly imposing about the artist’s presence. In response to the question: “Patrick Aloysius Phelan, you are charged with conspiracy to defraud: how do you plead, guilty or not guilty?” he had answered: “Guilty” in a sonorous voice. The accent was residually Irish, the tone surprisingly authoritative.

Patrick Phelan and his associate, the art dealer James Duval, had both been charged with conspiracy to defraud and the evidence against them was incontrovertible. In the artist’s case, a half-finished copy of a Modigliani nude with a photo of a missing original had been retrieved from his North London studio, and a painting sold as a Derain at auction for £16m had appeared in a video of the artist at work. In the dealer’s case, a police raid on his basement flat in Chelsea had revealed, hidden among a large collection of ‘genuine’ Phelans, three further forgeries of works by Alexei von Jawlensky, Albert Marquet and Maurice de Vlaminck. The five canvases had been key exhibits in court.

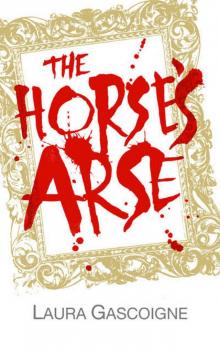

The Horse's Arse

The Horse's Arse